How can you ensure research data is FAIR?

There is a difference between storing and archiving data. Storing refers to putting the data in a safe location while the research is ongoing. Because you are still working on the data, the data still change from time to time: they are cleaned, and analysed, and this analysis generates output. As the image below illustrates, storing could be like cooking a dish: you are cleaning and combining ingredients.

Archiving, on the other hand, refers to putting the data in a safe place after the research is finished. The data are in a fixed state, they don’t change anymore. Archiving is done for verification purposes: so others can check that your research is sound. Or: it is done so that others can reuse the resulting dataset. There is also a difference between archiving and publishing, but in essence, archiving and publishing happen at a similar moment and for both, data do not change anymore.

This illustration is created by Scriberia with The Turing Way community. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807

Selecting Data for Archiving

There are various reasons to archive your data: replication, longitudinal research, data being unique or expensive to collect, re-usability and acceleration of research inside or outside your own discipline. It is VU policy to archive your data for (at least) 10 years after the last publication based on the dataset. Part of preparing your dataset for archiving is appraising and selecting your data.

Make a selection before archiving your data

During your research you may accumulate a lot of data, some of which will be eligible for archiving. It is impossible to preserve all data infinitely. Archiving all digital data leads to high costs for storage itself and for maintaining and managing this ever-growing volume of data and their metadata; it may also lead to decline in discoverability (see the website of the Digital Curation Centre). For those reasons, it is crucial that you make a selection.

Remove redundant and sensitive data

Selecting data means making choices about what to keep for the long term, and what data to archive securely and what data to publish openly. This means that you have to decide whether your dataset contains data that need to be removed or separated. Reasons to exclude data from publishing include (but are not limited to):

- data are redundant

- data concern temporary byproducts which are irrelevant for future use

- data contain material that is sensitive, for example personal data in the sense of the GDPR, like consent forms, voice recordings, DNA data; state secrets; data that are sensitive to competition in a commercial sense. These data need to be separated from other data and archived securely

- preserving data for the long term is in breach of contractual arrangements with your consortium partners or other parties involved

In preparing your dataset for archiving, the first step is to determine which parts of your data are sensitive, which can then be separated from the other data. Redundant data can be removed altogether.

Different forms of datasets for different purposes

Once you have separated the sensitive data from the rest of your dataset, you have to think about what to do with these sensitive materials. In some cases they may be destroyed, but you may also opt for archiving multiple datasets. For example, you may want to archive your dataset in more than one form depending on the purpose. For example:

- One for reusability to share

- A second one that contains the sensitive data, and needs to be handled differently.

For the first, the non-sensitive data can be stored in an archive under restricted or open access conditions, so that you can share it and link it to publications. For the second, you need to make a separate selection, so the sensitive part can be stored safely in a secure archive (a so-called offline or dark archive). In the metadata of both archives you can create stable links between the two datasets using persistent identifiers.

What to appraise for archiving

There are several factors that determine what data to select for archiving. For example, whether data are unique, expensive to reproduce, or if your funder requires that you make your data publicly available. This might also help you or your department to think about a standard policy or procedures for what needs to be kept, what is vital for reproducing research or reuse in future research projects.

More information on selecting data:

- Tjalsma, H. & Rombouts, J. (2011). Selection of research data: Guidelines for appraising and selecting research data. Data Archiving and Networked Services (DANS).

- Digital Curation Centre (DCC): Whyte, A. & Wilson, A. (2010). How to appraise and select research data for curation. DCC How-to Guides. Edinburgh: Digital Curation Centre.

- Research Data Netherlands: Data selection.

Data Set Packaging: Which Files should be Part of my Dataset?

A dataset consists of the following documents:

- Raw or cleaned data (if the cleaned data has been archived, the provenance documentation is also required)

- Project documentation

- Codebook or protocol

- Logbook or lab journal (when available, dependent on the discipline)

- Software (& version) needed to open the files when no preferred formats for the data can be provided

See the topic Metadata for more information about documenting your data.

Depending on the research project it may be that more than one dataset is stored in more than one repository. Make sure that each consortium partner that collects data also stores all necessary data that is required for transparency and verification. A Consortium Agreement and Data Management Plan will include information on who is responsible for archiving the data.

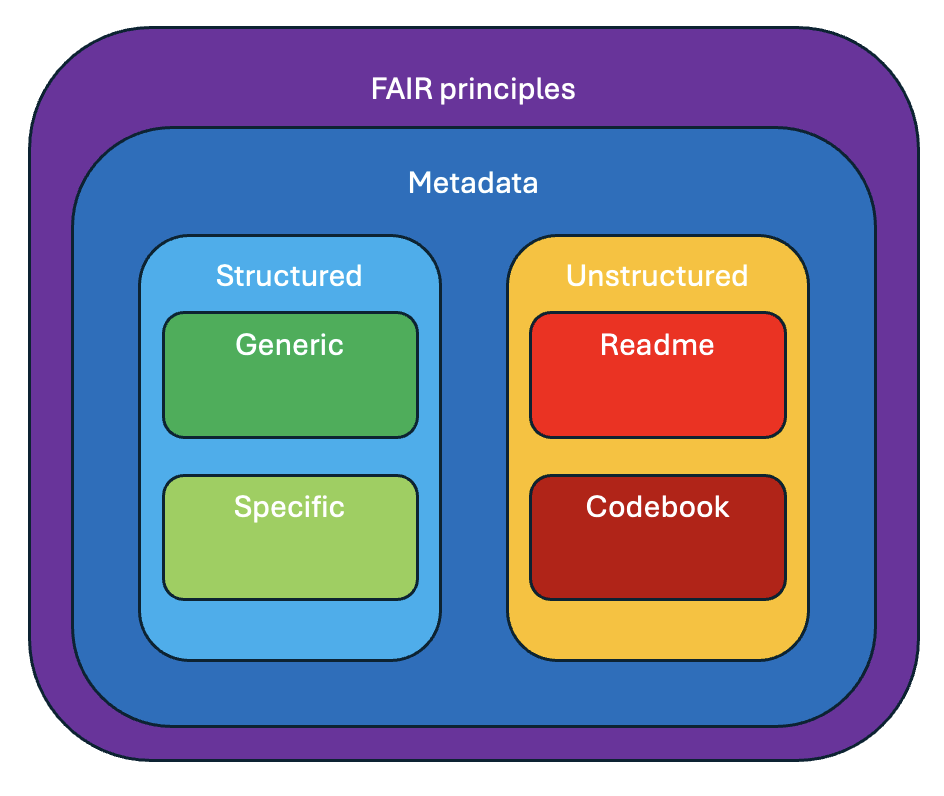

By creating documentation about your research data you can make it easier for yourself or for others to manage, find, assess and use your data. The process of documenting means to describe your data and the methods by which they were collected, processed and analysed. The documentation or descriptions are also referred to as metadata, i.e. data about data. These metadata can take various forms and can describe data on different levels.

An example that is frequently used to illustrate the importance of metadata is the use of the label on a can of soup. The label tells you what kind of soup the can contains, what ingredients are used, who made it, when it expires and how you should prepare the soup for consumption.

When you are documenting data, you should take into account that there are different kinds of metadata and that these metadata are governed by various standards. These include, but are not limited to:

- FAIR data principles: a set of principles to make data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable.

- Guidelines for unstructured metadata: mostly research domain-specific guidelines on how to create READMEs or Codebooks to describe data.

- Standards for structured metadata: generic or research domain-specific standards to describe data.

The CESSDA has made very detailed guidance available for creating documentation and metadata for your data.

FAIR data principles

The FAIR data principles provide guidelines to improve the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse of digital assets. The principles emphasise machine-actionability, i.e., the capacity of computational systems to find, access, interoperate, and reuse data with none or minimal human intervention.

More information can be found in the section about the FAIR data principles.

Unstructured metadata

Most data documentation is an example of unstructured metadata. Unstructured metadata are mainly intended to provide more detailed information about the data and is primarily readable for humans. The type of research and the nature of the data influence what kind of unstructured metadata is necessary. Unstructured metadata are attached to the data in a file. The format of the file is chosen by the researcher. More explanation about structured metadata can be found on the metadata page.

README

A README file provides information about data and is intended to ensure that data can be correctly interpreted, by yourself or by others. A README file is required whenever you are archiving or publishing data.

Example of READMEs

Codebook

A Codebook is another way to describe the contents, structure and layout of the data. A well documented codebook is intended to be complete and self-explanatory and contains information about each variable in a data file. A codebook must be submitted along with the data.

There are several guides for creating a codebook available:

- Creating a codebook - Kent State University

- Creating a codebook - for researchers at VU Amsterdam Faculty for Behavioural and Movement Sciences

- Codebook - Amsterdam Public Health

- DDI-Codebook - Data Documentation Initiative Alliance

Metadata provide information about your data. Structured metadata are intended to provide this information in a standardised way. The structured metadata are readable for both humans and machines. It can be used by data catalogues, for example DataCite Commons.

The standardisation of metadata involves the following aspects:

- Elements: rules about the fields that must be used to describe an object, for example the

title,authorandpublicationDate. - Values: rules about the values that must be used within specific elements. Controlled vocabularies, classifications and Persistent Identifiers are used to reduce ambiguity and ensure consistency, for example by using a term from a controlled vocabulary like the Medical Subject HEadings (MeSH) as a

subjectand an Persistent Identifier such as an ORCID to identify aperson. - Formats: rules about the formats used to exchange metadata, for example JSON or XML.

Metadata standards

Metadata standards allow for easier exchange of metadata and harvesting of the metadata by search engines. Many certified archives use a metadata standard for the descriptions. If you choose a data repository or registry, you should find out which metadata standard they use. At VU Amsterdam the following standards are used:

- Yoda uses the DataCite metadata standard

- DataverseNL uses the Dublin Core metadata standard

- VU Amsterdam Research Information System PURE uses the CERIF metadata standard

Many archives implement or make use of specific metadata standards. The UK Digital Curation Centre (DCC) provides an overview of metadata standards for different disciplines. The list is a great and useful resource in establishing and carrying out your research methodology.

Controlled Vocabularies & Classifications

Controlled vocabularies are lists of terms created by domain experts to refer to a specific phenomenon or event. Controlled vocabularies are intended to reduce ambiguity that is inherent in normal human languages where the same concept can be given different names and to ensure consistency. Controlled vocabularies are used in subject indexing schemes, subject headings, thesauri, taxonomies and other knowledge organisation systems. Some vocabularies are very internationally accepted and standardised and may even become an ISO standard or a regional standard/classification. Controlled vocabularies can be broad in scope or very limited to a specific field. When a Data Management Plan template includes a question on the used ontology (if any), what is usually meant is: is there a specific vocabulary or classification system used? The National Bioinformatics Infrastructure Sweden gives some more explanation about controlled vocabularies and ontologies here. In short, an ontology does not only describe terms, but also indicates relationships between these terms.

Examples of controlled vocabularies are:

- CDWA (Categories for the Description of Works of Art)

- Getty Thesaurus of Geographic names

- NUTS (Nomenclature of territorial units for statistics)

- Medical Subject HEadings (MeSH)

- The Environment Ontology (EnvO)

Many examples of vocabularies and classification systems can be found at the FAIRsharing.org website. It has a large list for multiple disciplines. If you are working on new concepts or new ideas and are using or creating your own ontology/terminology, be sure to include them as part of the metadata documentation in your dataset (for example as part of your codebook).

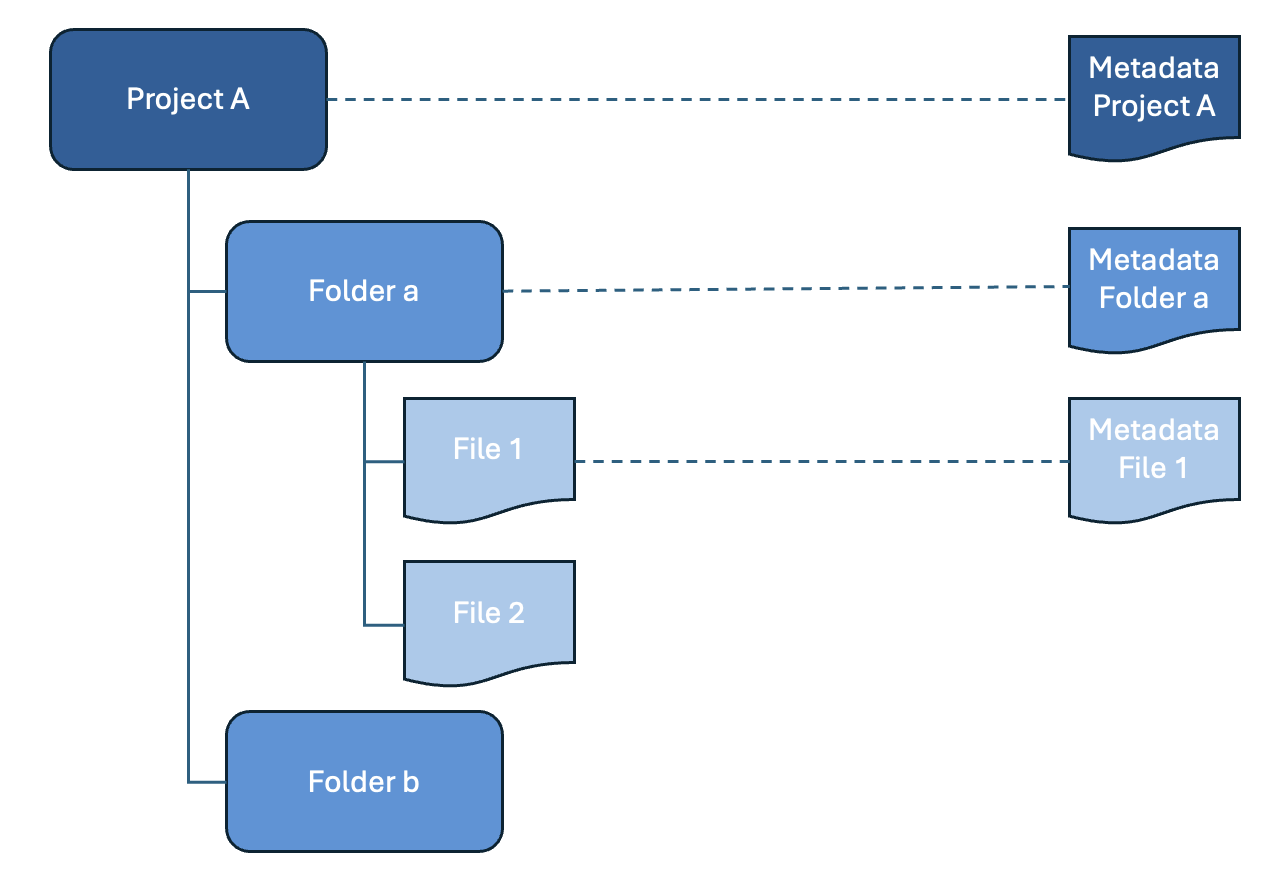

Metadata levels

Finally a distinction can be made on the level of description. Metadata can be about the data as a whole or about part of the data. It can depend on the research domain and the tools that are used on how many levels the data can be described. In repositories like Yoda and DataverseNL it is common practice to only create structured metadata on the level of the data as a whole. The Consortium of European Social Science Data Archives (CESSDA) explains this distinction for several types of data in their Data Management Expert Guide.

Dataset registration

When you want to make sure that your dataset is findable it is recommended that the elements of the description of your dataset are made according to a certain metadata standard that allows for easier exchange of metadata and harvesting of the metadata by search engines. Many certified archives use a metadata standard for the descriptions. If you choose a data repository or registry, you should find out which metadata standard they use. At VU Amsterdam the following standards are used:

- DataverseNL and DANS use the Dublin Core metadata standard

- VU Amsterdam Research Portal PURE uses the CERIF metadata standard

Many archives implement or make use of specific metadata standards. The UK Digital Curation Centre (DCC) provides an overview of metadata standards for different disciplines. The list is a great and useful resource in establishing and carrying out your research methodology. Go to the overview of metadata standards. More important tips are available at Dataset & Publication.